An Historical Tale of Love, Suicide and Failed State

Is the history repeating itself in Egypt of the 21st century?

The Ancient Egyptian civilisation existed for over 4000 years. The varying documentation is mostly engraved on coffins, tombs, and temples walls and written on papyri. The Dynastic period started approximately at 3200BC, and ended at 30BC by the death of Cleopatra. Power struggle within and between different official and greed, corruption and violence, and chaos were in evidence then as they are today. The historians divide this period into 31 Dynasties or families, in addition to the Macedonians and Ptolemaic Dynasties.

Over this long history, the civilisation was interrupted at 3 occasion with periods of statelessness with chaos and weak governance known as the Intermediate Periods. This divided the history into 4 Kingdoms[1]; Old, Middle, New and Late Kingdoms. The Dynasties from 3ed to the 6th are generally known as the Old Kingdom.

Egypt’s 6th Dynasty traditionally marks the end of the Old Kingdom of Ancient Egypt into the darkness of the First Intermediate Period[2]. They ruled from Memphis for 164 years and their pyramids and mortuary temples and funerary monuments were built at Saqqara. Some historians include the 7th and 8th Dynasties within the Old Kingdom.

The last three rulers of the 6th Dynasty were Pepi II and his two children Merenre II and Nitocris.

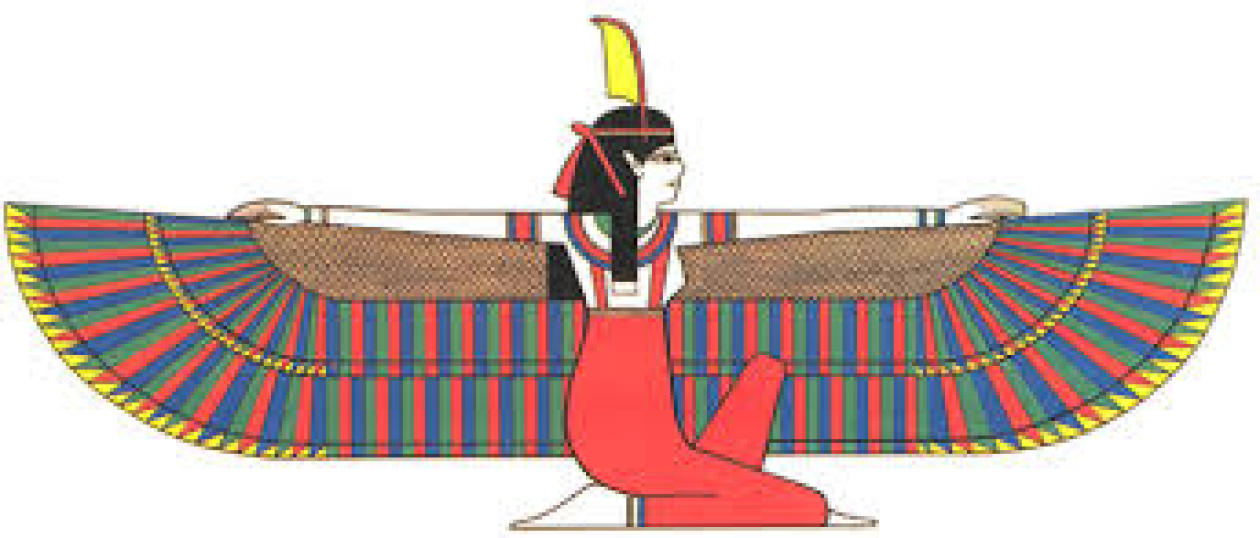

Citizens of today’s civilisations tend to consider our ancient ancestors as primitive, barbaric, and inept. Nitocris, a much less known Ancient Egyptian Sovereign Queen who ruled at the end of the 6th Dynasty 4200 years ago, was definitely otherwise. She used intelligence, and deception, and surprisingly logic and reason successfully before our modern civilisation and logicians invented the concepts. Most historians considers her the first female in history to rule a nation[3].

Nitocris had influenced the progress of the Egyptian civilisation dramatically. Her actions contributed to the First Intermediate Period that lasted for 125 years. The rule of the 7th, 8th, 9th, and 10th, and half of the 11th Dynasties were negligible. No significant archeological or political finds and limited literature records exist.

This is a brief summary of the events that lead to the failed state of the First Intermediate Period.

King Pepi II

According to Herodotus and Manetho and the Turin King-list, King Pepi II was the fifth ruler of the 6th Dynasty, ascending to the throne as a child. Most historians state that he reigned for 90 years. This would make Pepi II the longest ruling king of Ancient Egypt and in history. Some researchers are of the opinion that his rule was far less at 64 years only.

Pepi II mother Ankhesenmeryre II ruled during the early years of his life. Her name was never written within a cartouche. Her brother Djau served as a vizier during both Pepi I and Pepi II reigns, and helped her over these early years.

Queen Ankhesenmeryre and her brother were weak and corrupt, so was Pepi II.

The King’s court was the stage of intrigue and plots. Different members of the royal family, priests and high-ranking officials conspired to control power within the weak government and corrupt royals. The influence and authority shifted-away to the priests and high officials, and the effectiveness of the King weakened. The priests were more concerned with managing their expanded assets of land, temples, agricultural produce, rather than the affairs of the State.

Pepi II administration decentralised the role of vizier into one for Upper Egypt and one for Lower Egypt in Thebes, which weakened the power of the King in the Royal capital of Memphis. The powers of the nomarchs also grew and moved away from the central Royal Court to the regional noms and temples. Wealth shifted outside the control of the Royal House, the government, and the King. The regional leaders grew stronger. The nomarchs stopped paying taxation and their positions became hereditary. Large and expensive tombs for the reigning nomarchs, priests and other administrators appeared at many of the major provinces of Egypt.

During his long reign, Pepi II faced powerful, and rebellious, corrupt, and uncontrollable officials, priests and nomarchs, and noblemen. The interests of the governors became personal rather than national, creating independent feudal states and causing inter-nom wars, uncontrollable by the weak government and the Palace.

Over a period as long as 30-60 years, there were no notable funerary constructions. This caused a significant generational break of trained stonecutters, masons, and engineers. There were no major state project to maintain the practical skills for future generations.

Over time and with the advancing age of Pepi II and the dominance of corrupt officials, signs of failure of the state-system began to appear. The financial and political weakness of the Royal Court laid down the foundation for the collapse of the state and the initiation of the First Intermediate Period, the first in history. Pepi II was considered as the last substantive and verifiable ruler of Egypt before the political, social, judicial, and chronological chaos of the First Intermediate Period. There were no national major building programs for a period of 125 years.

With the limited archaeological finds, the following two rulers of the 6th Dynasty; Merenre Nemtyemsaf II and Nitocris, both were Pepi’s II children, are only known through the Abydos King-list, the Turin King-list and mentioned by Herodotus and Manetho. Merenre Nemtyemsaf II name is also mentioned on a stela discovered near the site of the pyramid of his mother, Queen Neith.

King Merenre II

After the death of Pepi II, his son Merenre II inherited the throne of Egypt in 2184BC. Merenre II was married to his sister Nitocris and had no other siblings or children. It was troubled times for Egypt. For the first time in its recorded history, Egypt was in a state of disruption, weak government, and controlled by corrupt officials.

When Merenre II, aided with his wife/sister Nitocris, got into power after the death of Pepi II they were determined to recover the lost power of the Royal Court and to correct the status quo of the failing state and to strengthen the Sovereign’s hold on the country, and planned a national and royal and political recovery program.

As expected this conflicted with the recently empowered priests and nomarchs, and noblemen and disagreed with their interests. Herodotus wrote, seeing that their power and wealth were threatened by the new King and his wife, that the priests and the nomarchs plotted against Merenre II and killed him. They accused the King of entering the temple of the God and un-lit the candles of Osiris, and defiled the hallowed altars with the carcasses on it and thus offending the God of Gods. Offences that deserved execution by the public. This they succeeded in doing.

He ruled for 13 months.

With the long reign of Pepi II of almost 90 years all other heirs were dead, and with the death of Merenre II, Nitocris was persuaded to take on the throne and become the Sovereign Queen. She was the only living heir to Pepi II and was the wife/sister of Merenre II.

Queen Nitocris[4]

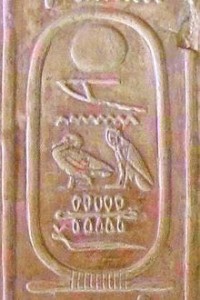

Nitocris historicity remains ambiguous though her name appears in a cartouche reserved for the Kings of Egypt. Her name Neterkare or Nitiqrty means, “the Soul of Re is Divine.” Her Prenomen[5] according to Manetho was Menkare. Herodotus called her Neterkare or Nitiqrty and her name in the Turin King List was Nitiqrty and in the Abydos King List Neterkare. Alternate Names were Nietkrety, Nitokerti. She is considered historically as the first[6] ever female Sovereign in history to rule a nation on her own right.

Herodotus[7] and Manetho[8] and the Abydos King-list and the Turin King-list show that Nitocris was the last ruler of the 6th Dynasty and followed her husband/brother King Merenre II. Most scholars agree that she ruled for 3 years and 4 months between 2184–2181BC. Manetho mentioned 12 years, and the Turin Canon 2 years and 1 month. Her burial place is unknown. Nitocris is not mentioned in any contemporary native Egyptian records. Nitocris left no archaeological records.

Nitocris rule defines the start of the dark period known as the First Intermediate Period. It is assumed that she contributed to its progress.

The dilemma of verifying Nitocris existence continues, including the gender of the name. Some commentators have suggested that the name is masculine denoting a “he.” Some authorities now suggest that the name “Nitocris” was confused with that of a male pharaoh named Neitiqerty Siptah. A fragment of the Turin King List was initially thought to refer to a queen of the Nineteenth Dynasty under the Egyptian name of Nitiqreti, was recently re-considered to belong to the 6th Dynasty portion of the King-list, thus appearing to confirm both Herodotus and Manetho of the historicity of Nitocris.

From the existing information, it is reasonable to assume that she did indeed exist. It might be, though, difficult to be unequivocal in the absence of archeological evidence. Without more evidence her historicity will continue to be debatable.

Nitocris initial political career role was as a head of the Civil Service during the rule of Pepi II, her father. This gave her knowledge of the running of the State.

On ascension to the throne, she recognised through her experience that the chaos that existed during her father rule and was beginning to recover with the rule of Merenre II and herself was foundering again.

The widowed Queen was also determined to punish the courtiers involved in the murder, and avenge her lover/husband/brother/King. Recognising the power of the priests and their influence on the masses, she tread very slowly and prudently making sure her secret is not discovered and avoiding any potential risks, setbacks, or adversaries.

Like her ancestors before her, Nitocris was a keen builder. Before the era of her father Pepi II, they had built massive pyramids and tombs, and temples for the gods, and palaces, with expansive, cool, and beautifully decorated underground chambers.

But her means were limited. There was a significant loss of trained professions of stonecutters, masons, and engineers that would last for the entire duration of the First Intermediate Period. Nonetheless she collected as many as she could master.

With the resolve to revenge her husband’s death and her enthusiasm for building, she constructed large underground banqueting chamber connected through a secret conduit to the Nile river.

Four years later and on completion of the banqueting chamber, she invited those who were involved in the murder of her lover/brother/husband/King. They were enthralled with the decoration, the statues, the decorated walls, the smell of incense scattered everywhere and enjoyed the varieties of wine and delighted themselves with the dancers and music.

It was a feast like nothing they ever seen before.

During the feast with all the guests heavily inebriated, and after ordering her staff of musician, dancers and guard out of the way to leave the chamber and lock the doors, the Queen commanded the subterranean chamber flooded.

She successfully avenged hundreds of priests, governors, civil servants and judges whom she determined were responsible for her husband killing.

The following days were not what she had expected.

The off springs and employees of the dead officials revolted and demanded revenge.

Queen Nitocris without hesitation decided to join her lover/husband/brother/King in the eternal afterlife. In order to escape vengeance, she suffocated herself in the smoke of a room full of embers assuring the preservation of her body to ensure eternity.

With the absence of any heir to the throne and the killing of the most senior members of the priesthood, the nomarchs, the noblemen and the civil servants, and the judges it is inconceivable to imagine what she had anticipated and the ensuing national chaos after this massacre. It is possible, though, that she did not plan to kill herself and use her civic experience to continue building the country with new recruits whom she trusted and did not have a grudge against, and young priests whom she can mold and control their political views and actions.

But when she recognised the possibility of vengeance of the masses, that is when she decided on this final action.

What happened after Nitocris death was nothing less than disaster that culminated in the collapse of the greatest civilisation that ever existed. It ended the reign of the 6th Dynasty of Ancient Egypt and the period in history known as the Old Kingdom, and started the dark period of the First Intermediate Period in earnest.

The 7th to the middle of the 11th Dynasties were weak, and had no significant archeological projects to show.

This failed state lasted for 125 years from ca. 2181–2055 BC before it recovered.

Nitocris was the Sovereign Queen to rule a land and the first to help destroying it. This revengeful Queen, ruled ca 2148–2144BC.

Comments:

The problem with the historicity of Nitocris as a regal or Sovereign Queen made few authorities to postulate that she being a female would be a possible cause of not including her name from the Kings records or its possible subsequent erasure. This is highly unlikely in Ancient Egypt, where womanhood was never a barrier to any rights even to rule in these early days of the civilisation.

It is not unreasonable to assume that a “female” Sovereign Queen who was known to have contributed to the collapse of the civilisation of Egypt and involved in driving the country into the darkness of the First Intermediate Period with its crimes, instability, lawlessness and internal wars for over 125 years, and committing suicide, would not be mentioned in the official records of the State.

The same would be the assumptions of her husband/brother/King Merenre II who was said to have un-lit the candles of Osiris, and defiled the hallowed altars with the carcasses on it and thus offending the God of Gods.

The poor documentation during the 7th to the 11th Dynasties and the limited archeological findings of Merenre II and Nitocris could also explain the incomprehensibility of including in history a King who offended Osiris and defiled his altars, and a Sovereign Queen who intentionally killed hundreds of Egyptians in a rage of revenge, and sinking the country into 125 years of instability and chaos and lawlessness. Taking into consideration the absence of substantive archeological information of the 7th to the 10th and half of the 11th Dynasties, the absence of information about Nitocris would not be unpredictable.

Manetho assigns 70 kings[9] ruling 70 days to the 7th Dynasty, thereby reflecting the chaos prevailing at the end of the Old Kingdom. The disorder and lawlessness deepened into anarchy, vandalism, social and temples destruction, and inter-nom wars.

Egypt required 125 years to recover after this disaster.

Egypt in the 21st century.

Mubarak ruled Egypt from 1981-2011 almost 30 years and created a corrupt weak government with a shift of wealth away from the people to a handful of members of his family, officials, and friends, who created their personal social and financial empires.

The weak and poor central government lost control and responsibilities of the economy, education, health, and the judicial system with no Nile water strategy or consistent Foreign Policy.

The weak Mubarak government and the subsequent governments after the 25th January 2011 revolution were unable to rescue the public and return the wheels to where it should be and could not help the people who became aggressive, uncooperative and immoral to get their rights, effectively taking the law into their own hands and creating enemies within the society.

Poverty, ignorance, and criminality spread.

The First Intermediate Period

The First Intermediate Period is also known as the “dark period” of Ancient Egypt history. It spanned approximately 125 years, from ca. 2181–2055 BC following the collapse of the 6th Dynasty. The dynasties from 3ed to the 6th are generally known as the Old Kingdom. The 7th and 8th dynasties are sometimes included in the Old Kingdom.

The archaeological features of 7th to the 10th and half of the 11th Dynasties are negligible. The political status was lawless and chaotic, with widespread wars between noms. The temples were plundered and vandalised and the artwork destroyed.

During this dark period, the governments were roughly divided between two competing power bases. One in Lower Egypt at Heracleopolis south of Faiyum and one in upper Egypt at Thebes. Most noms became more powerful and influential and independent from the King.

The collapse of political stability and peace was a gradual process with several triggering events. The extremely long reign of Pepi II for 90 years resulted into a weak government and corruption within the royal circle. He outlived almost all his heirs but two, bringing about problems with succession.

The provincial Governors acquired hereditary rights culminating into inter-family and inter-nom fighting over power in the provinces. Besides erecting their own tombs and monuments, the nomarchs often raised armies and fleets to dominate other noms with no concern of the central power.

This was further heightened with low levels of Nile inundation for many years over this period resulting in a drier climate and lower crops and famine across Egypt.

The weak central governments were unable to take responsibility and could not help the people who turned to their local nomarchs, effectively causing each nom to become an independent feudal state.

A further disruption was partly caused by religion. Upper Egypt proclaimed Amun as the King of the gods, and lower Egypt holding Ra in that position. The later creation of the combined God Amun-Ra was an obvious effective compromise to achieve peace.

By the middle of the 11th Dynasty the chaos ended with the Theban kings victorious and the country was once again unified.

Suicide in Ancient Egypt.

Suicide in Ancient Egypt was rare. For over 3000 years of the dynastic Egypt, there is no archaeological evidence of suicide nor religious discriminatory effects on those who killed themselves.

Few written documents exist. In these tales there is no condemnation of the act of suicide as morally wrong. The attitudes towards suicide varied and changed over time, from place to place, and from person to person. Some considered that suicide was a humane way to escape intolerable hardship.

In Ancient Egypt, the public also knew suicide and documented a handful of incidents.

The most frequently quoted were the suicides in the aftermath of the assassination attempt against Ramses III. The guilty conspirators including Queen Tiye’s son, Prince Pentawer, were condemned to death but were allowed to take their own lives, may be as a mark of leniency. In the same trial the former butler Pebes punishment was to have his nose and ears cut off, but he killed himself, probably unable to bear his shame.

Over the Dynastic Royal period of Ancient Egypt, Nitocris and Cleopatra were the only royals to commit suicide, and in both there was a love story. Queen Nitocris to avenge the murder of her husband/brother and Queen Cleopatra VII committed suicide in order not to be shamed by Octavian’s in a public triumph in Rome.

On the other hand in the 500 years of civilisation of ancient Rome, 5 emperors committed suicide; Gordian I, Maximian, Nero, Otho and Quintilus, and in all it was because of military failures.

Most of the documented Ancient Greek suicides were philosophers, not royalties.

In the Tale of Princes Ahura, prince Naneferkaptah, the son of King Merenptah went into a quest to retrieve the Book of Thoth. At the orders of Thoth, both Naneferkaptah sister/wife Princess Ahura and their son Merab drowned. Determined not to go back to the royal palace without them, Naneferkaptah decided to drown himself and not go back in disgrace.

Threats of killing oneself usually demanding help is also documented with a woman called Isidora, worried about the ill health of her child, wrote to her husband Hermias “Do anything, postpone everything, and come. preferably tomorrow. The baby is ill. It has become thin. It is already two hundred days [since you went away(?)]. I fear it will die in your absence. Know for sure: if it dies in your absence, be prepared that you do not find me hanged.”

The Eloquent Peasant Khun-Anup the hero of the famous story, threatened the judge Rensi son of Meru to report him to the God of the underworld Anubis unless he got his legal rights and justice. He was implying that he would commit suicide to do so.

It is natural to expect that the causes of suicide then were different from what is in the 20th and 21st centuries.

The method of suicide in Ancient Egypt also varied. Some by asphyxiation, others throw themselves before crocodiles or drowned. Queen Cleopatra committed suicide by poison and Queen Nitocris by asphyxiation. Both kept there bodies intact to ensure eternal life with the Gods.

Nitocris in literature.

There are several literary works about Nitocris starting early in the twenties century, yet she remains rarely known. Initially her historicity was not recognised but recent evidence suggest that it might actually be true based on accounts by Herodotus and Manetho.

An early-published literal work of Queen Nitocris was in the twenties of the last century by the celebrated writer Tennessee Williams.[10] He was 16 years of age when he published in “Weird Tales” magazines in 1928 “The Vengeance of Nitocris” stating that she revenged the killing of her husband.

Also the Nobel laureate Naguib Mahfouz in the novel “Rhodopis of Nubia,[11]” the Queen Nitocris promised revenge for her murdered King/husband/brother by saying “I will heap such revenge upon your enemies, that time will recount the tale of it for generations to come.”

Nitocris is also mentioned in other stories by H. P. Lovecraft, “The Outsider”[12] and “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs”[13] as an evil queen reigning over ghouls and other horrors. None of these stories are historical.

Among other writers, Brian Lumley in a short story “The Mirror of Nitocris,” presented Nitocris as an evil force affecting the owner of the mirror. This is also not historical.

[1] Early Dynastic Period (1st–2nd Dynasties)

Old Kingdom (3rd–6th Dynasties)

First Intermediate Period (7th–11th Dynasties)

Middle Kingdom (12th–13th Dynasties)

Second Intermediate Period (14th–17th Dynasties)

New Kingdom (18th–20th Dynasties)

Third Intermediate Period (21st–25th Dynasties) (also known as the Libyan Period)

Late Period (26th–31st Dynasties)

[2] Some authorities consider the 7th and 8th Dynasties as part of the Old Kingdom.

[3] Nitocris was preceded as a Sovereign Queen by Queen Meryt-Neith1 of the first Dynasty 3000BC, who ruled as a caretaker Queen on behalf of her young son King Den for an unknown period.

1 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Merneith

[4] The Turin canon lists her after Pepi II and (possibly) Merenre II. The confusion is a reflection of the disintegration of the Old Kingdom, which led to the First Intermediate Period. Manetho is a bit suspect, as he asserts that Nitocris build the “third pyramid” at Giza (the one we attribute to Menkaure/Mycerinos). It’s possible that he confused the name of Men-kaw-re with Nitocris’ praenomen, Men-ka-re.

[5] Her Titulary Horus Name, Nebty Name, Golden Horus Names are not known.

[6] Nitocris was preceded by the Sovereign Queen Meryt-Neith who was a caretaker queen for her young son mmm during the first Dynasty.

[7] Herodotus recorded that Nitocris’ husband Merenre II was murdered. The Queen took her revenge on the murderers and then took her own life. Herodotus wrote:

Nitocris was the beautiful and virtuous wife and sister of King Metesouphis II (Merenre II), an Old Kingdom monarch who had ascended to the throne at the end of the Sixth Dynasty but who had been savagely murdered by his subjects soon afterwards. Nitocris then became the sole ruler of Ancient Egypt and determined to avenge the death of her beloved husband-brother. She gave orders for the secret construction of a huge underground hall connected to the river Nile by a hidden channel. When this chamber was complete she threw a splendid inaugural banquet, inviting as guests all those whom she held personally responsible for the death of the king. While the unsuspecting guests were feasting she commanded that the secret conduit be opened. As the Nile waters flooded in, all the traitors were drowned. In order to escape the vengeance of the Egyptian people she then committed suicide by throwing herself into a great chamber filled with hot ashes and suffocating

Herodotus also knew of Nitocris and briefly reviewed a part of her reign. In his Histories, Book II he said

“Next, the priests read to me from a written record the names of three hundred and thirty monarchs, in the same number of generations, all of them Egyptian except eighteen, and one other, who was an Egyptian woman. The story was that she ensnared to their deaths hundreds of Egyptians in revenge for the king her brother, whom his subjects had murdered and forced her to succeed; this she did by constructing an immense underground chamber, in which, under the pretence of opening it by an inaugural ceremony, she invited to a banquet all of the Egyptians whom she knew to be chiefly responsible for her brother’s death; then, when the banquet was in full swing, she let the river in on them through a large concealed conduit-pipe. The only other thing I was told about her was that after this fearful revenge she flung herself into a room full of ashes, to escape her punishment.”

Herodotus also wrote

“… [Nitocris] succeeded her brother. He had been the king of Egypt, and he had been put to death by his subjects, who then placed her upon the throne. Determined to avenge his death, she devised a cunning scheme by which she destroyed a vast number of Egyptians. She constructed a spacious underground chamber and, on pretence of inaugurating it, threw a banquet, inviting all those whom she knew to have been responsible for the murder of her brother. Suddenly as they were feasting, she let the river in upon them by means of a large, secret duct.”

Herodotus Histories II, Herodotus wrote

“Of her they said that desiring to take vengeance for her brother, whom the Egyptians had slain when he was their king and then, after having slain him, had given his kingdom to her, desiring, I say, to take vengeance for him, she destroyed by craft many of the Egyptians. For she caused to be constructed a very large chamber under ground, and making as though she would handsel it but in her mind devising other things, she invited those of the Egyptians whom she knew to have had most part in the murder, and gave a great banquet. Then while they were feasting, she let in the river upon them by a secret conduit of large size. Of her they told no more than this, except that, when this had been accomplished, she threw herself into a room full of embers, in order that she might escape vengeance.”

[8] Manetho described her as

“braver than all men of her time, the most beautiful of all women, fair skinned with red cheeks”

“She was the noblest and loveliest of the women of her time.” -Manetho

[9] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seventh_and_Eighth_Dynasties_of_Egypt

[10] The Vengeance of Nitocris” (Weird Tales, August 1928.

[11] Rhodopis of Nubia, Translated by Anthony Calderbank, The American University in Cairo Press, Cairo, New York, 2003. First published in Arabic 1943.

[12] Lovecraft, Howard P. (1984). “The Outsider.”

[13] Lovecraft, H. P. (2008). H. P. Lovecraft: Complete and Unabridged.